Jackie Robinson Day: Larry Doby Edition

Sports is meant to be entertainment, an escape from daily toils, our common love of the game binding us. Yet how can we be entertained when we look on the playing field and are so easily reminded about the lack of opportunity, the systems that create racial and gender bias?

Following the tradition that started in 2004, each Spring, on April 15th, Major League Baseball commemorates the anniversary of Jackie Robinson's MLB debut in 1947 by dressing every MLB player in the number 42, Robinson's since retired jersey number.

While Robinson wasn't the very first Black major league baseball player, he is correctly credited with breaking the color barrier in the "modern" era. The "modern" era, in MLB parlance, is a sanitized marketing term that refers to end of the "Gentleman's Agreement" of 1887, the period of 67 years where owners of both minor and major league teams secretly agreed to deny contracts to Black players.

Robinson's exceptional athletic ability and personal charisma combined with social conditions that finally overcame baseball's unwritten restriction on Black players in the leagues. Before Jackie stepped onto the field as a Brooklyn Dodger in 1947 the previous Black MLB players were a pair of brothers, Moses and Weldy Walker, who both played for the Toledo Blue Stockings of the American League way back in 1884.

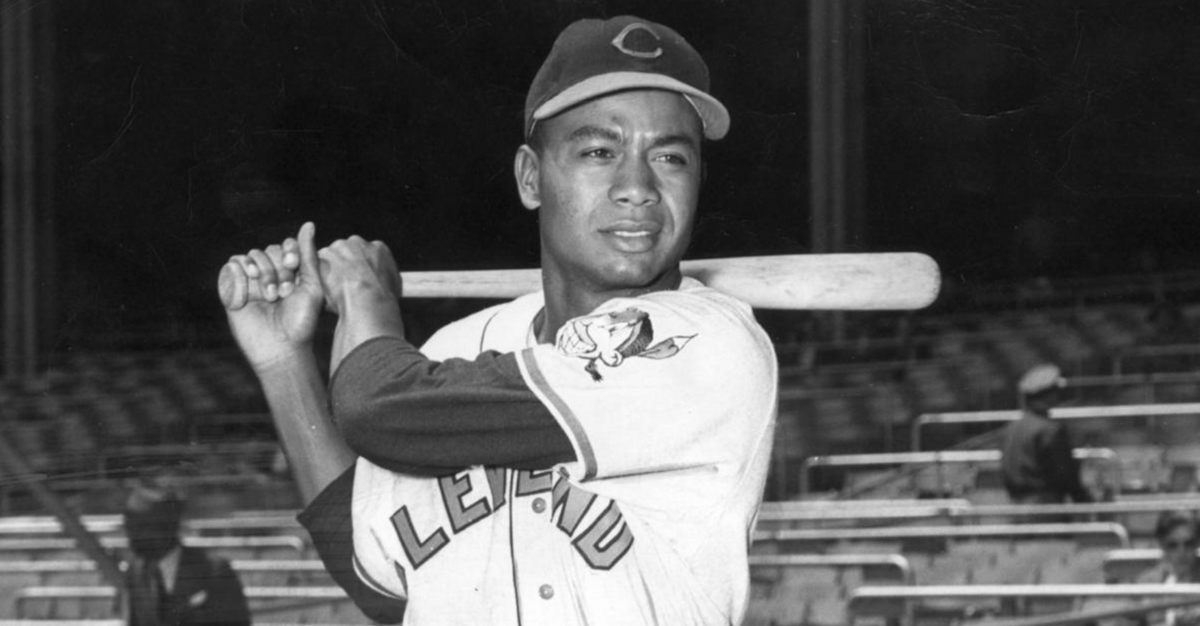

While Jackie was the first player after the end of the Gentleman's Agreement in the National League, it was Larry Doby, three months after Robinson's debut, who became the first Black player in the American league, signing with the Cleveland Indians in July of 1947. Doby was already a champion, having lead his prior team, the Newark Eagles, to the Negro league title in 1946. In 1948, Doby helped the Indians win the World Series, appearing in 121 games and batting over .300 for the season. Larry's legendary teammate during that championship year was another Black rookie, at the surprising age of 42, named Satchel Paige. Larry would go on to become a seven-time all-star center fielder, and lead the league in runs batted in and home runs in 1954, a year where he finished second in most valuable player votes.

Like Robinson, Doby dealt with countless and overt racism and bigotry throughout his career. Doby was born in the segregated South in 1923, and required to attend a Black only school in Camden, South Carolina. Heading into high school Doby moved to Patterson, New Jersey where he played baseball, football, and track. His Patterson Eastside high school football team won the state championships and were invited to play in Florida, however the promoter wouldn't allow Doby, the only Black player, to participate. His teammates boycotted the game in support of Larry.

When making his MLB debut and meeting his fellow teammates, several of them wouldn't shake his hand and two turned their back to him during introductions. It was five-time world series champion Joe Gordon who eased the tensions in the clubhouse when he asked Doby to play catch with him.

"I walked down that line, stuck out my hand, and very few hands came back in return.

- Larry Doby

The count of Black players steadily rose throughout and after the careers of both Robinson and Doby, peaking in 1975 around 19%. In 2023 that number has fallen to about 7%, far under representing Black athletes. According to USA Today's analysis of the 2023 starting rosters only 6.1% of players are Black, a decreasing trend in recent years. There are twice as many players from the Dominican Republic, a country with a population of only 11 million people, than there are Black players on starting rosters. In 2022, for the first time since 1950, three years after Robinson and Doby's debut, no US-born Black players competed in the World Series. Gentlemen's agreement indeed.

USA TODAY’s study revealed that five teams don’t have a single Black player on their major-league roster with nine other clubs having just one.

- Bob Nightengale, USA TODAY

The numbers are even worse in college baseball, which accounts for a bit more than 10% of MLB recruits. Per the NCAA's published data, if you remove HBCU colleges from the mix, only 3% of baseball athletes are Black and head coach positions account for a measly 1% of the job. Dusty Baker, of the Houston Astros, and Dave Roberts, of the Los Angles Dodgers, remain the only two MLB head coaches, the same as last year. Although Tony Beasley briefly held the interim manager role of the Texas Rangers for 48 games last season before he was replaced by veteran coach Bruce Bochy.

MLB needs to do much, much better. It must.

I look forward to Jackie Robinson's Day each year because it serves to me as a reminder of how much work still remains to be done to make athletics, and much broader than that, our society, more inclusive. Sports is meant to be entertainment, an escape from our daily toils, where a common love of the game binds us. Yet how can this be, when we look on the playing field and are so easily reminded about the lack of opportunity, reminded of the systems that create and sustain biases and grow divisions especially around race and gender? No, sport is not an escape from our reality, in fact, it's a symptom of it, just take a closer look.