Finding Raymond Carver In All Of Us

There is value in telling and in listening. If we remind ourselves to be aware, the bonds we seek can be strengthened and while we learn more about our friends, we are learning more about ourselves too.

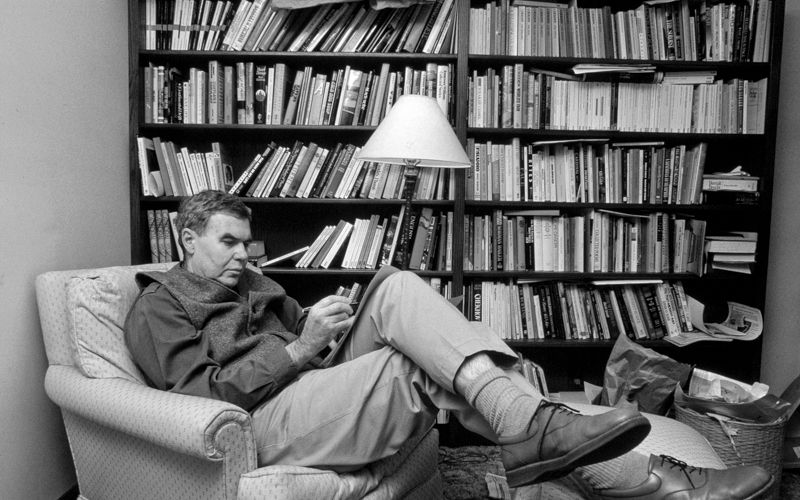

I've just completed the 43rd book I've read this year. It was a small collection of Raymond Carver short stories. I have only recently been introduced to Carver. It occurred while reading Jay Rubin's excellent book Haruki Murakami and the Music of Words, part biography, part analysis of Murakami's writing. As many of you may know, I'm a huge Murakami fan. Unfortunately, I've run out of English translations to read, so I have been working through the catalog of influencers he has referenced and the large number of books that he translated to Japanese throughout his career.

Carver's work shines a spotlight on the banal life of everyman, exploring relationships, boring jobs, and ultimately the restlessness that lives in all of us. Alcohol cost him his first marriage and contributed to his shortened life, many of his characters struggle with alcoholism too, and rocky relationships. The writing is raw, often unfinished, with hanging threads unresolved by a story's end. And his writing is powerful, even in its sparseness.

In Why Don't You Dance, Carver tells a story of a yard sale. The entire contents of a home have been placed in the front lawn, arranged as they were in the house: bed with his and her night stands, the buffed aluminum kitchen set, a big console tv on a coffee table, a potted fern. A young couple eventually stops, tries out the bed, listens to records, and shares a drink with, we presume, the male homeowner. They dance, all three of them, and the couple purchases several items on the cheap, no haggling.

Is this a moving sale? Is it a scorned husband taking revenge on his now divorced wife? Has this man simply gone off the deep-end? We don't know. Carver weaves this spell in a paltry seven pages, and it is memorable and mysterious.

In another story, The Calm, the protagonist describes his trip to the barber where several other patrons sit waiting for their haircuts. One man begins to tell a story of a hunting trip. He and his son shoot at a deer, the man wounding the deer, the son emptying his gun in a wild, excited volley, missing. The deers runs off. The man becomes irate and cuffs his son, giving him a concussion, while his son recovers, the sun begins to set and they fail to go find the deer. Another patron takes offense that the first didn't bother to track the deer, leaving it to the coyotes to find. An argument ensues, all the patrons leave in a huff. Mundane, and yet these are the types of stories we all carry with us, that surround the people we interact with everyday. It is the connected tissue we use to build relationships. A story we can relate to, one we envision telling others, even as it happens to us.

I gathered with a group of friends yesterday, some former co-workers. Past the initial greetings and How are you's, the dialog took on the familiar, comfortable tone of people sharing their stories: One had recently installed a wood pellet stove to heat his basement, two updated us on the gigs they have been playing with their band, another is starting a new job on Monday, one has put his house up for sale and moving to Colorado.

It's these moments that have a currency. There is value in telling and in listening. If we remind ourselves to be aware, the bonds we seek can be strengthened and while we learn more about our friends, we are learning more about ourselves too.

If you are interested in exploring Raymond Carver's writings, a good place to start is What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.